Casinos That Were Never Casinos

Posted on: April 25, 2024, 06:02h.

Last updated on: May 9, 2024, 12:11h.

The word casino didn’t always refer to a gambling establishment. Deriving from casa, which is Italian for house, it originally denoted a small villa or summer house.

During the 19th century, the word evolved to encompass social clubs and other buildings where people gathered for private celebrations or public recreation, which could but didn’t normally include games of chance.

Below is a list of the most famous American businesses named casino in this sense of the term.

The word casino has evolved so far beyond its original meaning that the website for every one of these businesses or historic sites includes some variation of the sentence, “no, there are no slot machines here,” which is no doubt the first question every first-time visitor asks.

But as much as the meaning of casino has changed over 200 years, its derivation from casa is still why today’s casinos still get referred to as “the house.”

Catalina Casino

Avalon, Calif.

The largest and by far most noticeable structure on the island from the sea, the Catalina Casino was opened by chewing gum tycoon William Wrigley Jr. in 1929, to mark the 10-year anniversary of his purchase of Santa Catalina Island.

Nearly a century later, the landmark stands as a reminder of the days when millions made the 26-mile trip across the sea to enjoy a movie, dinner, and dancing here.

Today, it still functions as a movie theater and a ballroom for private and municipal receptions.

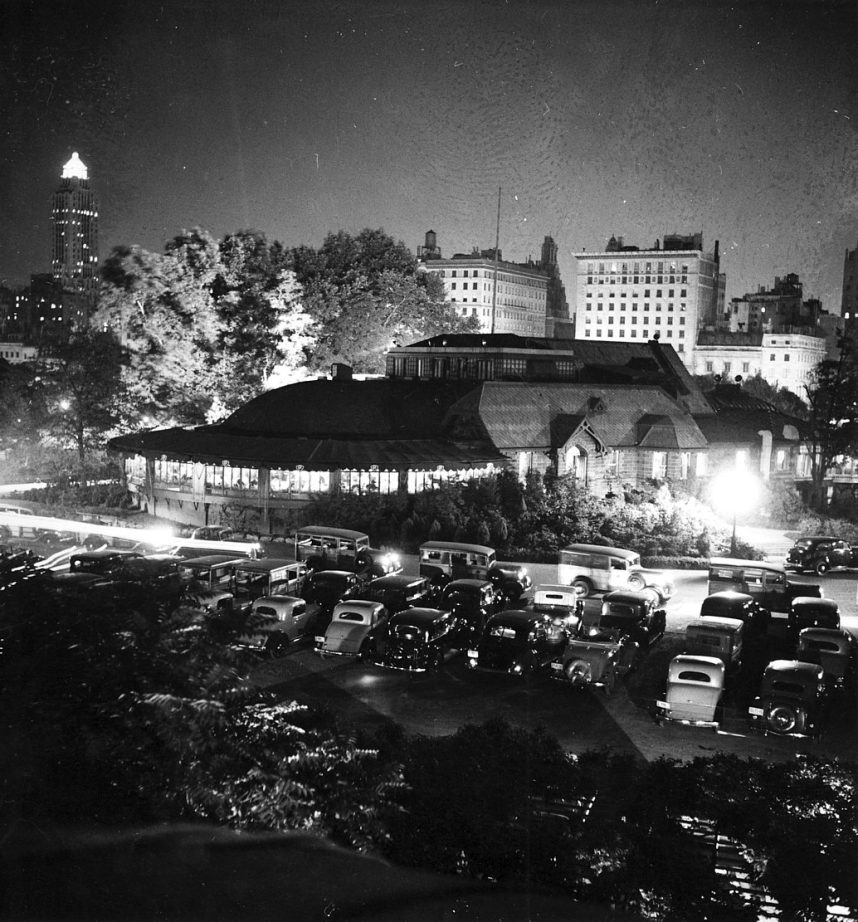

Central Park Casino

New York, NY

Manhattan’s hottest nightclub was once located inside Central Park, near Fifth Avenue south of 72nd Street.

Opened in 1864, six years after the park, the Casino (originally called the Ladies’ Refreshment Salon) catered to unaccompanied female visitors to the park — and also to the males interested in accompanying them out of the park.

In 1929, the Central Park Casino received a $9 million (in today’s dollars) makeover after its lease was reassigned to hotelier Sidney Solomon, with financing allegedly via gangster Arnold Rothstein, who was murdered before reopening night.

The Casino, as it was known, became the most expensive restaurant in New York, its regulars including railroad tycoon William Vanderbilt, banker Robert Lehman, and showbiz mogul Florenz Ziegfeld. Its after-dinner parties raged until 3 a.m. almost every weekend for five years.

Though Prohibition wouldn’t end until 1933, alcohol somehow always flowed freely here. Anyone who had a problem with that was welcome to take it up with New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker, who had a standing table reservation and even an office in the building. (According to the New York Times, he spent more time there than at City Hall.)

A special investigation into Walker’s acceptance of $1 million in bribes led to his forced resignation, and voluntary escape to Paris, in 1932. His populist successor, Fiorello La Guardia, and his tyrannical (and racist) parks commissioner, Robert Moses, hated Walker and every reminder of his corrupt administration. They served the Casino’s management an eviction order in 1934.

Everything was demolished except stained-glass windows later installed in the park’s 86th Street police station, though they disappeared years ago.

In 1936, the lot on which it stood was turned into a playground. Today, it functions as SummerStage.

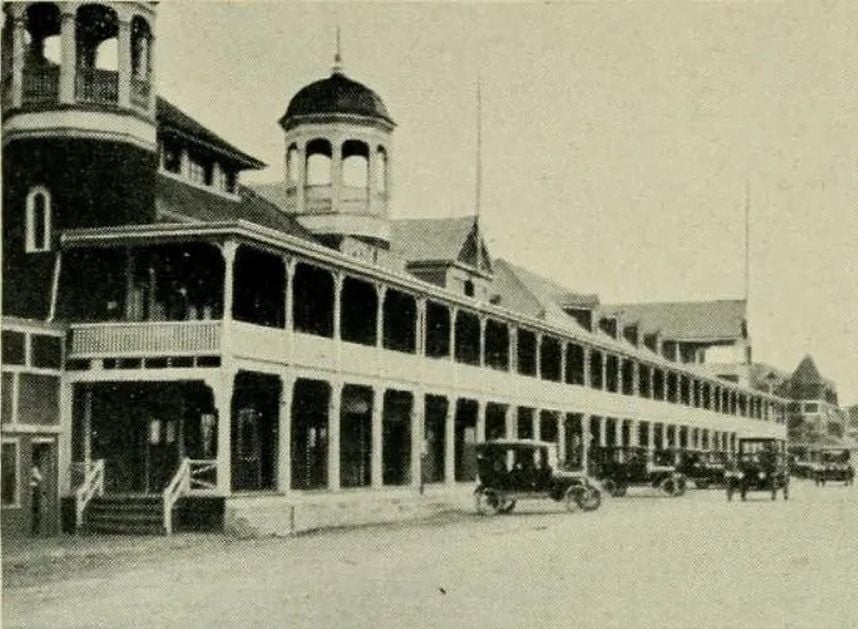

Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom

Hampton, NH

This noncasino casino was opened on July 4, 1899, by Wallace D. Lovell, who owned the Exeter, Hampton, and Amesbury Street Railway Company, with the hope of bringing more business and tourism to Hampton.

It worked after it was expanded in 1927 to add the 5,000-seat ballroom, the largest dance floor in New England.

The ballroom quickly gained a national reputation by attracting national acts including Bing Crosby and Duke Ellington. When rock n’ roll pushed big bands and crooners off their bandstands, it drew a young Led Zeppelin in 1969 and an infamous Jethro Tull and Yes double bill on July 8, 1971.

It was infamous because 4,000 unticketed fans showed up, rioting and scaling the walls to climb in through the windows. The National Guard was called in, and the town of Hampton banned rock concerts for several years.

After a facelift in the 1970s, the venue reopened as Club Casino, and one of the new owners began booking up-and-coming acts including U2 and Melissa Etheridge.

In the ’90, the ballroom’s original facade was restored, along with its original name. The venue continues to book top-name concerts from April to November of each year.

Casino Hall

La Grange, Texas

Casino Hall was built in 1881 by the Casino Society. The group, formed by German immigrants displaced by the German Revolutions of 1848, sought the company of others sharing their language, customs, and pursuits in this small, and somewhat small-minded, southern city.

Having outgrown the original wooden meeting place they built in 1858, the society raised $12,000 ($450,000 today) to build this two-story brick German school, performance hall, and gathering place.

By then, anti-German sentiment had mellowed somewhat and the facility was used by the local population at large, including the Ladies Cemetery Association, the Knights of Honor, and, because not all small-mindedness had mellowed, the La Grange Minstrel Club.

By 1884, the city decided to take over Casino Hall and make it a public school. It paid the Casino Society $6,500 ($200,000 today) for the building. In 1924, the La Grange Independent School District took control of the building but, in 1924, sold it back to the city (for $7,500), which used it to house its fire department (first floor) and City Hall (second floor).

City Hall moved to a new location in 1968, and the fire department bailed in 1992, leaving the building to become the La Grange Senior Citizen Center until 2006.

Casino Hall remained vacant until 2014, when a multimillion-dollar renovation transformed it into today’s Historic Casino Hall, which features a visitors bureau and performing arts center.

Gulfport Casino

Gulfport, Fla.

This is actually the third version of this structure, the first of which was built in 1906 to host town meetings, parties, and church services.

That got destroyed in a 1921 hurricane, and its replacement — erected hastily on stilts over the Boca Ciega Bay — met its end after President Franklin Roosevelt’s Civil Works Society authorized the construction of a new one, along with a new pier, to avoid a similar fate.

Gulfport Casino 3.0 opened in 1934 with a solid maple dance floor and 10,000 square feet of dancing, socializing, and bingo space.

In 1949, this noncasino casino also became the site of a murder when Lawrence Minutoli, a 68-year-old barber and former Chicago resident, shot and killed Isabelle Marchand, a 43-year-old widow, as she exited a bingo party.

According to statements given by Minutoli to police, Marchand once had him arrested for molesting her and, confusingly, also owed him $500 ($6,500 today).

“I asked her to pay me the bill she owes me,” Minutoli stated, according to the St. Petersburg Times. “She tells me there’s nothing to talk about, so I shot her. She made trouble for me for 10 years. Now she’ll make trouble no more.”

The Historic Gulfport Casino Ballroom, as it’s now officially known, was added to the list of National Historic Places in 2014. It’s now operated by the City of Gulfport’s Cultural Facilities Department, which rents it out for dances.

Sandwich Casino

Sandwich, Mass.

Not many people alive today remember our final noncasino casino. Opened in 1884, it featured a portico, two anterooms, a large gallery, a raised bandstand, and, most impressively for the time, indoor toilets.

The building hosted roller skating and dances, the lighting provided by gas jets.

For its grand opening, the Sandwich Casino imported an orchestra all the way from Boston. Boston was only 60 miles south, but this was two years before the automobile was invented.

In 1848, when the railroad came to Sandwich, the casino hosted a celebration banquet for 1,200 people. Another big celebration marked the town’s 250th anniversary in 1889.

Unfortunately, a 1938 hurricane weakened and doomed the structure. Its last public event was a play called “Hay Fever” on Aug. 5, 1941. It was torn down either in 1944 or 1945, though no one remembers for sure.

Did we miss a non-casino casino you know about? Email corey@casino.org.

Related News Articles

‘Daily Wager’ Ratings Soar, but ESPN Reportedly Boots Host

Sphere Entertainment Posts Big Q2 Loss as Revenue Soars

Most Popular

The Casino Scandal in New Las Vegas Mayor’s Closet

This Pizza & Wings Costs $653 at Allegiant VIP Box in Vegas!

Sphere Threat Prompts Dolan to End Oak View Agreement

MGM Springfield Casino Evacuated Following Weekend Blaze

Most Commented

-

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Casinos Pump in Extra Oxygen

— November 15, 2024 — 4 Comments -

Chukchansi Gold Casino Hit with Protests Against Disenrollment

— October 21, 2024 — 3 Comments

Last Comments ( 4 )

Thanks so much, guys!!

Chestnut Ridge park in Orchard Park NY had a 'casino', a place of entertainment. Cool stone building with picnic tables and giant fireplaces. Great warming place in winter next to the toboggan runs and sledding hill.

Corey check out Roger Williams Park Casino in Providence,RI

There was a ‘casino’ on the waterfront of Walled Lake in the city of Walled Lake. Originally built in 1925. It was a popular teen dance spot until it burned down in 1985