LOST VEGAS: Block 16, Sin City’s Only Official Red-Light District

Posted on: May 9, 2024, 01:09h.

Last updated on: September 9, 2024, 10:02h.

Google “Block 16” and “Las Vegas” and you may think this article is about an expensive food hall at the Cosmopolitan on the Strip. It is about the human appetite for expensive vices, but food isn’t among them.

Exactly how and when Las Vegas first got the nickname “Sin City” is up for debate. However, Block 16 was most certainly where.

When the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad auctioned off the parcels of its land that became Las Vegas on May 15, 1905, they were gridded out into 40 blocks. Each consisted of 32 lots, 25 by 140 feet, fronted by an 80-foot-wide street and bisected by a 20-foot-wide alley.

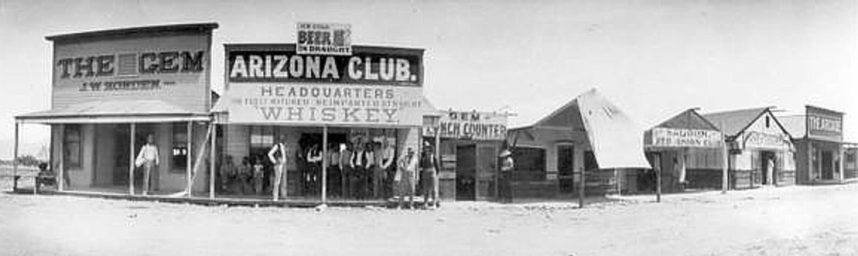

Block 16, located on First Street between Ogden and Stewart avenues, was designated as the only place (outside of hotels) where alcohol could legally be sold.

Gambling and prostitution quickly joined gin consumption in Las Vegas’ only official red-light district, where six hotels and 11 saloons opened to cater to all three demands in varying degrees.

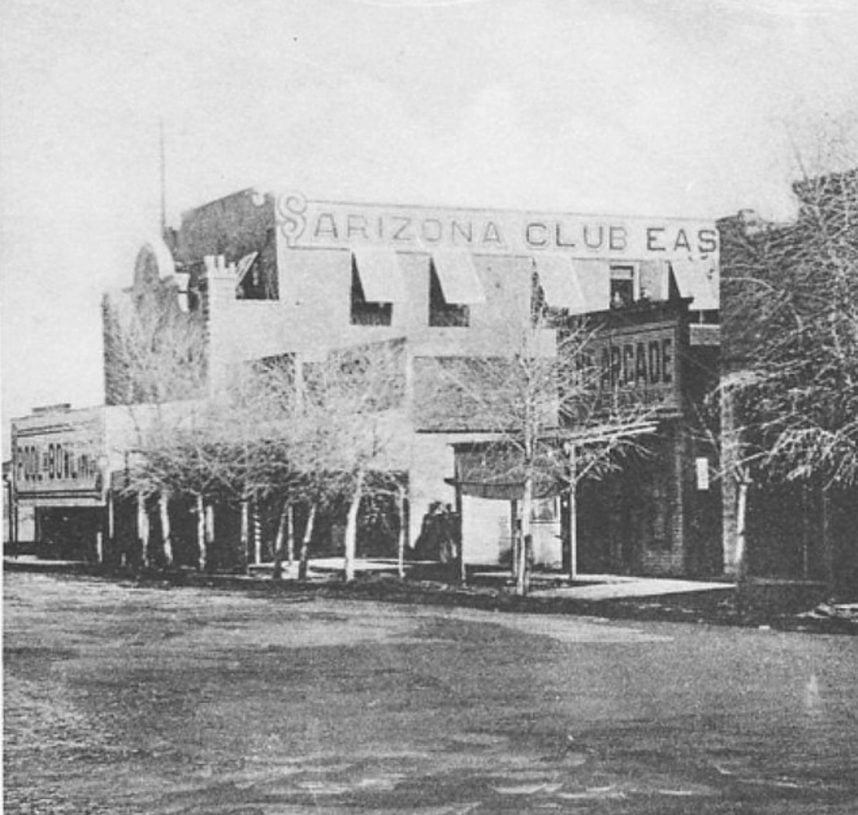

“The Queen of Block 16” was the nickname bestowed on the classier Arizona Club. With its $20K mahogany bar, it was the first casino in Las Vegas, and also the first casino to build its own “hotel.” (More on why “hotel” appears in quotes in a bit.)

In 1909, unbeknownst to all but students of Las Vegas history, gambling was outlawed in Nevada. In 1920, the 18th Amendment then prohibited the sale of alcohol across the US. And though neither law would be repealed until the 1930s, there was little trouble finding games of chance or booze on Block 16 throughout this period.

Vice Principles

Counterintuitively, sex was the most consistently legal vice available on Block 16. Though prostitution is illegal in today’s Las Vegas, and everywhere else in Clark County, this wasn’t the case during most of the first half of the 20th century.

In fact, brothels in Block 16 were only illegal if their owners failed to pay their $500 annual license fees to the city, or any of the prostitutes skipped their required weekly medical exams.

And that’s why the Arizona Club’s “hotel” was really a second story of small rooms exclusively for the use of working women and their gentlemen.

When passenger trains pulled into Las Vegas back then, their stops lasted 45 minutes, which was long enough for a “quickie.”

“Each of those places had a madam as the operator,” former Las Vegas city manager George L. Ullom told Jamie Coughtry for the author’s 1989 UNLV oral history project, “Politics and Development in Las Vegas, 1930s-1970s.”

“I don’t suppose that there were over 40 girls involved,” Ullom said. “In the warmer months, the girls would stand out in front of the place to whistle at a possible customer.”

Though Ullom denied ever being one of those customers, he said he recalled Block 16 “very well as a small child and then later as an adult, when I was a policeman.”

Hookers and Blowback

Ironically, the re-legalization of Las Vegas gambling in 1931 galvanized the operators of the town’s bordello-less casinos against prostitution, which they considered competition for their customers’ money and time.

But the death warrant for Block 16 was signed by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1941, after the US entered WWII. The May Act banned prostitution near military bases, leaving the determination of “near” up to base commanders.

Following passage of this new law, the Army Air Corps issued a stern warning to Las Vegas’ city’s commissioners: ban prostitution on Block 16 or all of Las Vegas will be declared off limits to servicemen.

Earlier that same year, Nellis Air Force Base had opened 8 miles away, as the Las Vegas Army Air Field, and soldiers with off-duty passes crowded Block 16 by the hundreds every night.

The city commission caved, voting to revoke the liquor and gambling licenses of all saloons and hotels that refused to quit their bordello-ing.

And it was with that order that Las Vegas police chief Frank Wait resigned. (He thought Las Vegas would be better off with legal prostitution than illegal streetwalkers.)

“We went down and informed them all and closed them up,” said Ullom, who was among the police officers tasked with enforcing the new ordinance. “The day after the closing, it seems to me that there were two people that we brought out and took down and arrested, and that was the end of it.”

Though the May Act was lifted in 1948, Las Vegas officially cracked down on any bordello that reopened on Block 16, staging a series of raids in the early ’50s justified by the “public nuisance” that prostitution presented. (Click here to read about the history of legal prostitution elsewhere in Nevada.)

By later that decade, the majority of the saloons/bordellos on Block 16 had closed and were demolished.

“Most of these girls disappeared,” Ullom recalled, “but then it was open field for the hustlers.”

Today, more than 70 years later, the area is occupied by the California Hotel & Casino and a parking garage for Binion’s. And though the name “Block 16” still registers with tourists, it’s mostly as the Las Vegas home of Hattie B’s Hot Chicken.

“Lost Vegas” is an occasional Casino.org series spotlighting Las Vegas’ forgotten history. Click here to read other entries in the series. Think you know a good Vegas story lost to history? Email corey@casino.org.

Related News Articles

Westin Hotel Guest Has Luxury Watch Stolen in Las Vegas

Brutal Nevada Murder Linked to Prostitution

Most Popular

This Pizza & Wings Costs $653 at Allegiant VIP Box in Vegas!

Sphere Threat Prompts Dolan to End Oak View Agreement

MGM Springfield Casino Evacuated Following Weekend Blaze

Atlantic City Casinos Experience Haunting October as Gaming Win Falls 8.5%

Most Commented

-

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Casinos Pump in Extra Oxygen

— November 15, 2024 — 4 Comments -

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: The Final Resting Place of Whiskey Pete

— October 25, 2024 — 3 Comments

Last Comments ( 2 )

Reno didn't ban prostitution until about 1948. But other places in Washoe County offered convenient commuting to carnality...

Nice article. Thanks.