LOST VEGAS: Las Vegas Park Horse Track Stood Where Elvis AND The Beatles Would Perform

Posted on: September 7, 2023, 10:34h.

Last updated on: January 31, 2024, 08:07h.

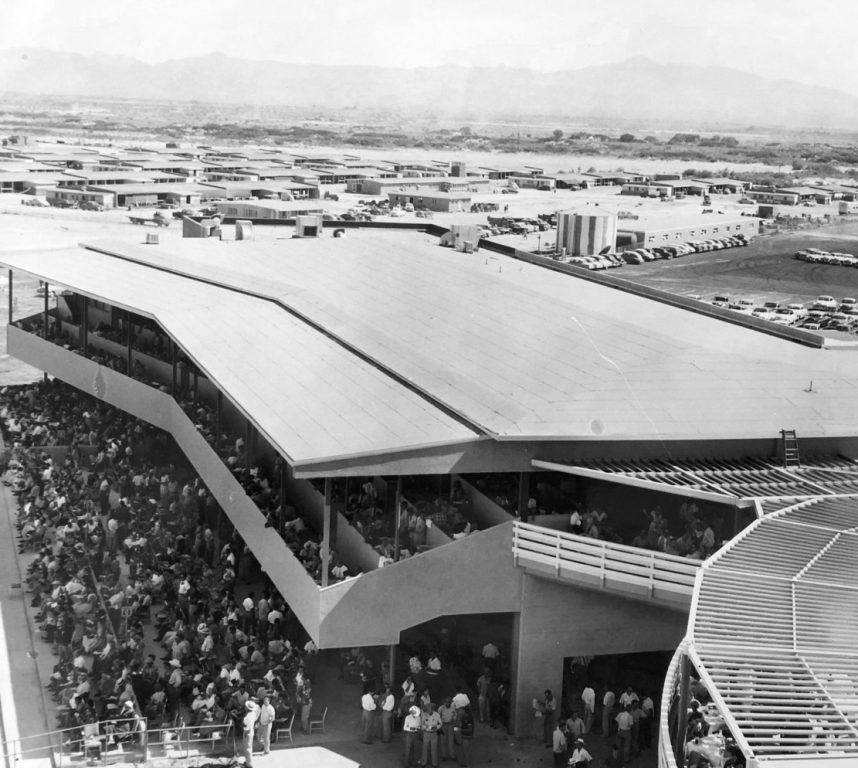

Las Vegas Park opened 70 years ago this week. And you can easily be forgiven for never having heard of the one-mile horse track that was located on the site of today’s Las Vegas Country Club, Las Vegas Convention Center, and Westgate Hotel.

That’s because it operated for a total of 13 days.

Las Vegas Park opened with giant aspirations on Sept. 4, 1953 for a 67-day inaugural meet. Its failure to meet those aspirations, or even to complete that schedule, is legendary.

It Seemed Like a Good Bet

Las Vegas’ birth as an entertainment and gambling mecca dovetailed perfectly with the ‘50s boom in Thoroughbred racing. In fact, Las Vegas Park even made history as America’s first racino. (The Las Vegas Gaming Commission permitted 165 slots at the racetrack.)

It was gorgeous for its day, too. The clubhouse and grandstand were painted pink to replicate Argentina’s Hipodromo Rosado. Virtually no expense was spared in its $4.5 million budget (more than $40 million today).

And its schedule fit neatly in-between the end of the Del Mar race meeting and the start of the Hollywood Park meeting.

This track seemed like a sure bet to host one of the premier Kentucky Derby prep races.

So how did something so perfect stumble out of the gate?

Major Blinders

Before the track ever opened, it already had a backstory tainted by corruption, embezzlement, and major blinders.

That backstory began with Joseph M. Smoot — a New York racing promoter who had an early hand in the success of the Santa Anita and Hialeah racetracks, and figured that meant he could do anything.

In 1948, Smoot purchased 750 acres of vacant land just east of the Strip from the Leigh Hunt estate at $750 per acre, and began constructing his dream a year later.

But a little more than a year after that, Smoot woke up in a nightmare. He was charged with three counts of embezzling $24K from the Las Vegas Thoroughbred Racing Association, over which he presided. During a hearing, a federal court judge reportedly asked Smoot to produce receipts or canceled checks for $500K that reportedly went missing without a trace.

Smoot responded: “You ever try to pay a politician with a check?”

Smoot remained under indictment until he died of natural causes in 1955, penniless, in a free room at the Grand Hotel.

Second Race

By 1953, Las Vegas Park was bought out of its first bankruptcy and completed by the Las Vegas Jockey Club, a new corporation headed by investors including Lou Smith and Al Luke. Counting on a ton of big-name horses, and their big-spending Southern California owners, the partners promised to award $1.9 million — the richest prize ever offered by a first-year track.

To take their bets, they opened the very first $500 betting window at a horse track.

When Las Vegas Park finally opened that Sept. 4, some of the horses came. (Among the 75 that ran was 15-time stakes winner Blue Reading.) But the big spenders were mostly AWOL. A devastatingly low take of $252,683 fell nearly $150K short of the $400K daily requirement for the racetrack to meet expenses.

And the local population couldn’t even fill the seats left by absentee tourists. Clark County had only 50,000 residents back then, compared to nearly 3.3 million today. In all, 8,200 paying customers occupied a space designed to hold 20,000.

Malfunctioning ticket booths, only one entrance that worked, and a major malfunction of the infield tote board didn’t help matters. After its third day open, the track closed for two weeks while a replacement board was installed, erasing what little momentum and word-of-mouth opening day generated.

After Las Vegas Park reopened, it didn’t log a single break-even day. When 4,000 customers wagered a total of $100K on Oct. 10, veteran racing journalist Pete Bonamy called it “one of the poorest showings by a racing crowd ever recorded.”

Las Vegas Park closed on Oct. 19, 1953, after racing only 13 programs.

“Racing needs population,” columnist Leon Rasmussen wrote in Thoroughbred Record magazine at the time, “and although Las Vegas does not hew to convention in very many ways, it is still not quite fabulous enough to sustain a track as pretentious as this one hoped to be.”

Beating a Dead Horse Track

Its stables were vacated in October 1953, though the complex was revived for another short but failed horseracing run the next year. The daily attendance recorded by the Las Vegas Turf Club in December 1954 was even more dismal than its predecessor — at times as low as 400. That experiment lasted seven weeks.

By January 1955, an oil magnate bought the racetrack out of its second bankruptcy for $2.65 million. But Joe W. Brown didn’t intend to build a third failed horseracing track. His thing was purchasing properties to hold onto for others. Two years earlier, he purchased the Horseshoe Club from his old Texas buddy, Benny Binion, so he could run it while Binion served four years in Leavenworth Penitentiary for tax evasion.

And Brown purchased Las Vegas Park for a similar reason. He was holding onto it while the City of Las Vegas and Clark County got its ducks in a row. Civic leaders wanted a portion of the land to build what eventually became the Las Vegas Convention Center, but didn’t have the funding at the time.

By January 1956, that deal was complete and the first convention center — a 6,300-capacity, silver-domed rotunda with an adjoining 90,000 square-foot exhibition hall — opened following Brown’s death three years later. On Aug. 20, 1964, it hosted the only Beatles concert staged in Las Vegas.

Vroom For Rent

While it awaited demolition, the renamed and still mostly intact Las Vegas Park Speedway was repurposed for auto racing. It hosted three major races: the AAA Champ Car event in 1954, the NASCAR Grand National Championship in 1955, and a United States Auto Club Grand Prix in 1959.

It also achieved cinematic immortality by serving as the setting for a racecar scene in the 1964 Elvis Presley movie, “Viva Las Vegas.”

In 1965, Brown’s estate sold most of the remaining property to National Equities Inc., which later used it to construct the Las Vegas Country Club along Joe. W. Brown Drive. Another 20 acres were sold to Clark County to expand the Convention Center.

Las Vegas Park was finally demolished in 1966. A year later, National Equities sold 65 of its former acres to Caesars Palace landlord Kirk Kerkorian to build the International Hotel — which meant that Las Vegas Park would enter history for a more unexpected reason…

Both Elvis and the Beatles would one day perform where it once stood.

“Lost Vegas” is an occasional Casino.org series featuring remembrances of Las Vegas’ lesser-known history. Click here to read other entries in the series. Think you know a good Vegas story lost to history? Email corey@casino.org.

Related News Articles

The Buildings Elvis Presley Left in Las Vegas

Casino.org’s Insider Tips For Las Vegas Visitors

Most Popular

Jackpot News Roundup: Two Major Holiday Wins at California’s Sky River Casino

PUCK, NO! Health Dept. Closes Las Vegas Wolfgang Puck Restaurant

Oakland A’s Prez Resigns, Raising Questions About Las Vegas Move

MGM Osaka to Begin Construction on Main Resort Structure in April 2025

Most Commented

-

UPDATE: Whiskey Pete’s Casino Near Las Vegas Closes

— December 20, 2024 — 33 Comments -

Zillow: Town Outside Las Vegas Named the Most Popular Retirement City in 2024

— December 26, 2024 — 31 Comments -

Oakland A’s Prez Resigns, Raising Questions About Las Vegas Move

— December 27, 2024 — 9 Comments -

Caesars Virginia in Danville Now Accepting Hotel Room Reservations

— November 27, 2024 — 9 Comments

Last Comment ( 1 )

Thanks Corey. Big racing fan...I would've thought Temps that time of year were a problem. The truly sad thing is they were ahead of the times. Every track wishes they'd brought in slot machines back then, specifically to attract females, but horseracing overall (except for the big events) has been in decline for decades. Thanks Corey, I had no idea Kevin Anderson