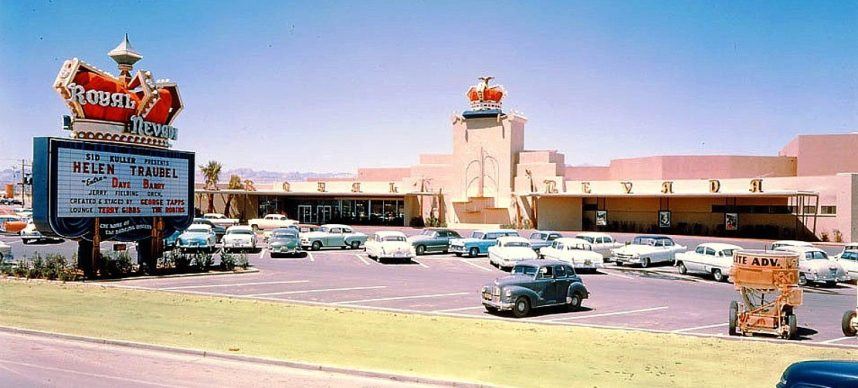

LOST VEGAS: Royal Nevada Casino Hotel, 1955-58

Posted on: November 18, 2024, 02:03h.

Last updated on: November 18, 2024, 09:18h.

Royal Road

Plans for the $2.5 million Royal Nevada were announced in 1953 by millionaire Miami, LA, and San Francisco hotelier Frank Fishman, who wanted to call it the Sunrise Hotel. It was located north of the Last Frontier and south of the construction site for the Starlight Hotel, which would be rebranded the Stardust following the death of its founder, Tony Cornero.

Fishman, 62, was granted a casino license even though he had no gaming experience. He told the Nevada Tax Commission — which until the Nevada Gaming Commission (NGC) was formed in 1959, approved all gaming licenses in the state — that he planned to hire a proper casino manager.

By August, construction began on what was rebranded, to better confer a sense of luxury, the Royal Nevada. The building was designed by Paul Revere Williams, who also architected the Moulin Rouge and La Concha Motel. Williams made the resort’s insignia the royal crown, a year before all of America began associating the identical symbol with Imperial brand margarine. One topped its road sign, another its main building.

Battle Royal

By the end of 1954, the construction company sued Fishman, seeking back pay. (Several years later, the Las Vegas Sun newspaper would sue him for $13,500 in unpaid advertising dating from this time.)

Then, on February 4, 1955, a month after the Royal Nevada was originally scheduled to open, Fishman’s new application for a gaming license was denied.

The application listed the two new Miami partners Fishman took on to run the casino: restaurateur Herbert “Pittsy” Manheim and Sam “Gameboy” Miller. Though the application didn’t list their mafia nicknames, tax commission investigators were sharp enough to identify them as the operators — along with mobsters “Big” Sam Cohen and Jack Friedlander — of Miami’s illegal Island Club. Before that, they discovered that Miller operated an illegal horse race wire in Michigan.

Fishman was also condemned for, as described by one commission member during the two-day hearing, “peddling his license” around to interest other licensees. The commission concluded that all three applicants were “totally undesirable citizens for Nevada,” a finding that made newspaper headlines across the country.

A thoroughly humiliated Fishman and his partners were relieved of their stock and replaced as owners and gambling licensees by other shareholders, including Albert Moll and Roberta Mae Simon of St. Louis, Miami businessmen Barnett Rosenthal and Joe Liebman, and Miami attorney Herman Kohen.

Fishman was allowed to remain the casino’s landlord, but his dream of ever operating a casino was over.

Royal Sendoff (No. 1)

Somehow, the Royal Nevada survived to its grand opening, which saw Helen Traubel, a soprano in the New York Metropolitan Opera, give a stellar performance highlighted by “Brahms’ Lullaby (Cradle Song).”

But business was significantly less stellar after that. That’s because the Royal Nevada was one of three Las Vegas casino resorts to open on the newly renamed Las Vegas Boulevard within a six-week period at a time when demand for additional rooms was on the decline.

The Dunes and Riviera not only both had bigger and more impressive casinos than the Royal Nevada, with its 10 table games and 54 slots, but much more impressive names on their marquees.

With a limited budget and a reputation primarily for going out of business, the Royal Nevada attracted C-level headliners to its Crown Room. These included Italian opera singer Anna Maria Alberghetti, comedian Dave Barry (no, not that one), and Robert Alda, the movie actor who would go on to significantly more fame just being TV star Alan Alda’s dad.

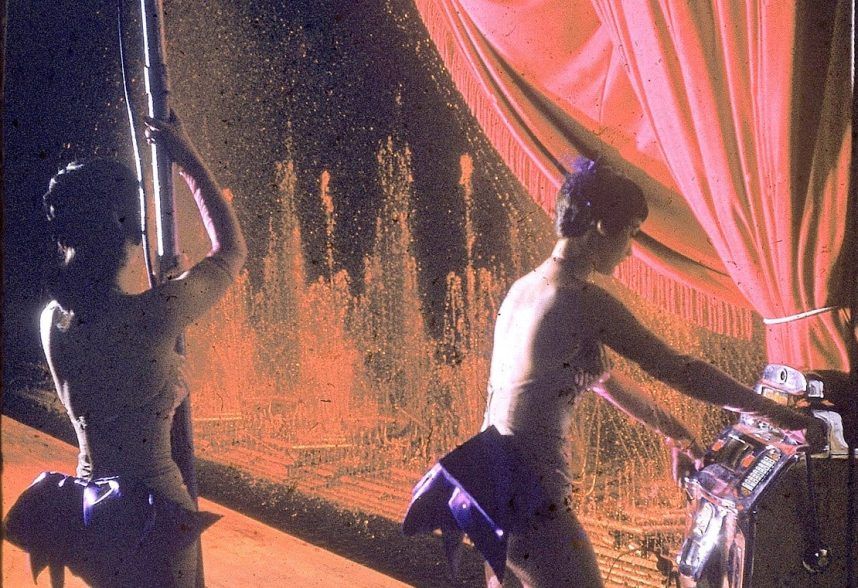

The property’s only real attraction was the Dancing Waters, Las Vegas’ gasoline-powered first fountain show. In fact, most of the property’s entertainers actually opened for the fountains.

January 30, 1958, was actually the third time the Royal Nevada went out of business. The first was on New Year’s Day 1956. By December 1955, the new property’s casino had failed to win enough cash to cover its license fees and the back wages it owed to a local labor union.

So, the property was leased to Jake Kozloff, a casino manager with more experience. Its 233-room hotel reopened on February 23, 1956. By June, it was taken over by its next-door neighbor. Though the Royal Nevada retained its name, it existed merely as an overflow annex for the Last Frontier.

The Last Frontier leased the casino to a group of its former licensees, including Kozloff and T.W. Richardson, who were approved for a gaming license in January 1957, though one of their co-applicants, Detroit mobster Maurice Friedman. was forced to withdraw his name.

The casino reopened on February 1, 1957. Two months later, yet more bad news arrived in the form of colossal competition from the Tropicana. Nicknamed “the Tiffany of the Strip,” it was the most luxurious and expensive ($15 million) casino resort Las Vegas had seen to that point.

Royal Scandal

In August, the Nevada Gaming Board slapped the Royal Nevada with an eight-count complaint alleging “improper operation.” Among its charges were a lack of adequate funds and cheating.

It seems that one of its blackjack dealers was allegedly observed, on two occasions, peeking at cards and dealing second cards. Thus, the Royal Nevada became the first major Nevada casino accused of cheating.

In response, the tax commission ordered the casino closed, for the second time, on December 9, 1957, though its hotel was allowed to remain open.

A creditor committee successfully appealed to allow the casino to operate during Christmas and the New Year’s holidays — only for the purpose of paying debts to around 200 creditors. The commission closed the casino for the third and final time in January.

On March 5, 1958, agents with the Bureau of Internal Revenue closed the hotel portion for not paying its 1957 income taxes.

Broken Crown

Six months after the Royal Nevada closed, the Stardust finally opened next door, following three years of funding delays. A year after that, the Stardust’s new operator, mob-connected Desert Inn co-owner Moe Dalitz, purchased the Royal Nevada and relegated it to serving as the Stardust’s convention center.

It was renamed the Stardust Auditorium.

Boyd Gaming finally put the building out of its misery in 2006, demolishing it to make way for a casino resort, Echelon Place, that would never be built due to the Great Recession two years later.

Today, the Royal Nevada’s forgotten footprint is part of Resorts World’s.

“Lost Vegas” is an occasional Casino.org series spotlighting Las Vegas’ forgotten history. Click here to read other entries in the series. Think you know a good Vegas story lost to history? Email corey@casino.org.

Thanks to Vintage Las Vegas, we now know that this record was set, and is still held, by the Desert Spa casino, which lasted for only 57 days in 1958 before being remade into a shopping center that burned down in 1961. (It’s now the Fashion Square Shopping Center at Las Vegas Boulevard South and Convention Center Drive.)

We apologize for the error!

Related News Articles

LOST VEGAS: The Frank Rosenthal Show

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Howard Hughes Ran the Mob Out of Town

VEGAS MYTHS BUSTED: Bugsy Introduced Mob to Vegas in 1946

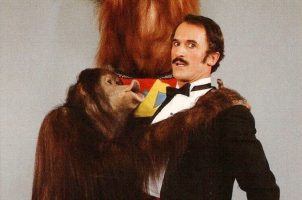

LOST VEGAS: Bobby Berosini’s Orangutans

Most Popular

FTC: Casino Resort Fees Must Be Included in Upfront Hotel Rates

Genovese Capo Sentenced for Illegal Gambling on Long Island

NBA Referees Expose Sports Betting Abuse Following Steve Kerr Meltdown

UPDATE: Former Resorts World & MGM Grand Prez Loses Gaming License

Most Commented

-

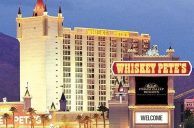

UPDATE: Whiskey Pete’s Casino Near Las Vegas Closes

— December 20, 2024 — 32 Comments -

Caesars Virginia in Danville Now Accepting Hotel Room Reservations

— November 27, 2024 — 9 Comments -

UPDATE: Former Resorts World & MGM Grand Prez Loses Gaming License

— December 19, 2024 — 8 Comments -

FTC: Casino Resort Fees Must Be Included in Upfront Hotel Rates

— December 17, 2024 — 7 Comments

No comments yet