VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: ‘Fear and Loathing’ Really Happened

Posted on: November 29, 2024, 08:04h.

Last updated on: November 27, 2024, 12:03h.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “Vegas Myths Busted” publishes new entries every Monday, with a bonus Flashback Friday edition. Today’s entry in our ongoing series originally ran on March 3, 2023.

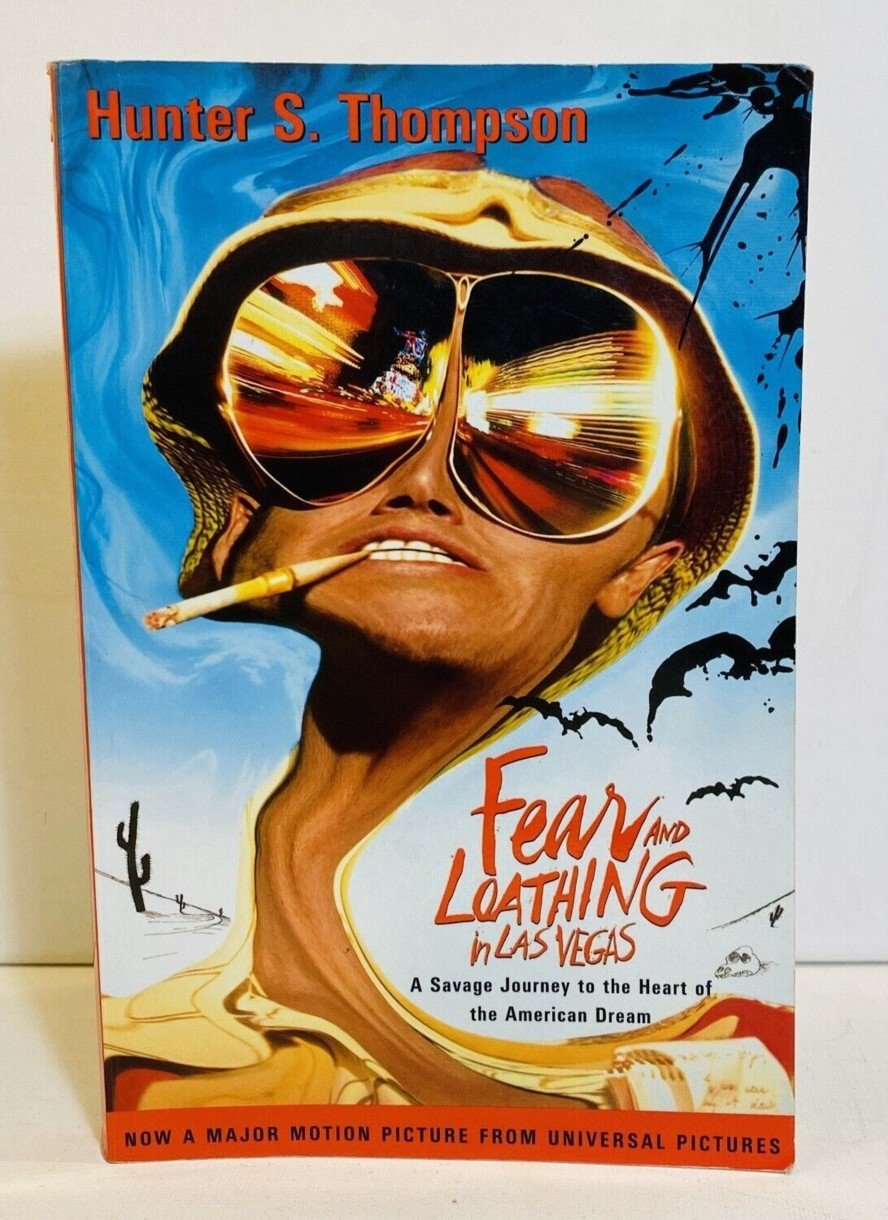

Hunter S. Thompson, who died by suicide 18 years ago last Monday, is famous for being a gonzo journalist. So, many of his fans regard his book, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, as a journal of events that actually occurred.

Actually, that’s not so much their fault, since Random House published the author’s 1972 masterwork under the category of general nonfiction. But Thompson never claimed any of the events described in it were true.

The fact that neither of his main characters was a real person should have been the first clue. The story is narrated by one Raoul Duke, whose traveling companion/attorney is Dr. Gonzo.

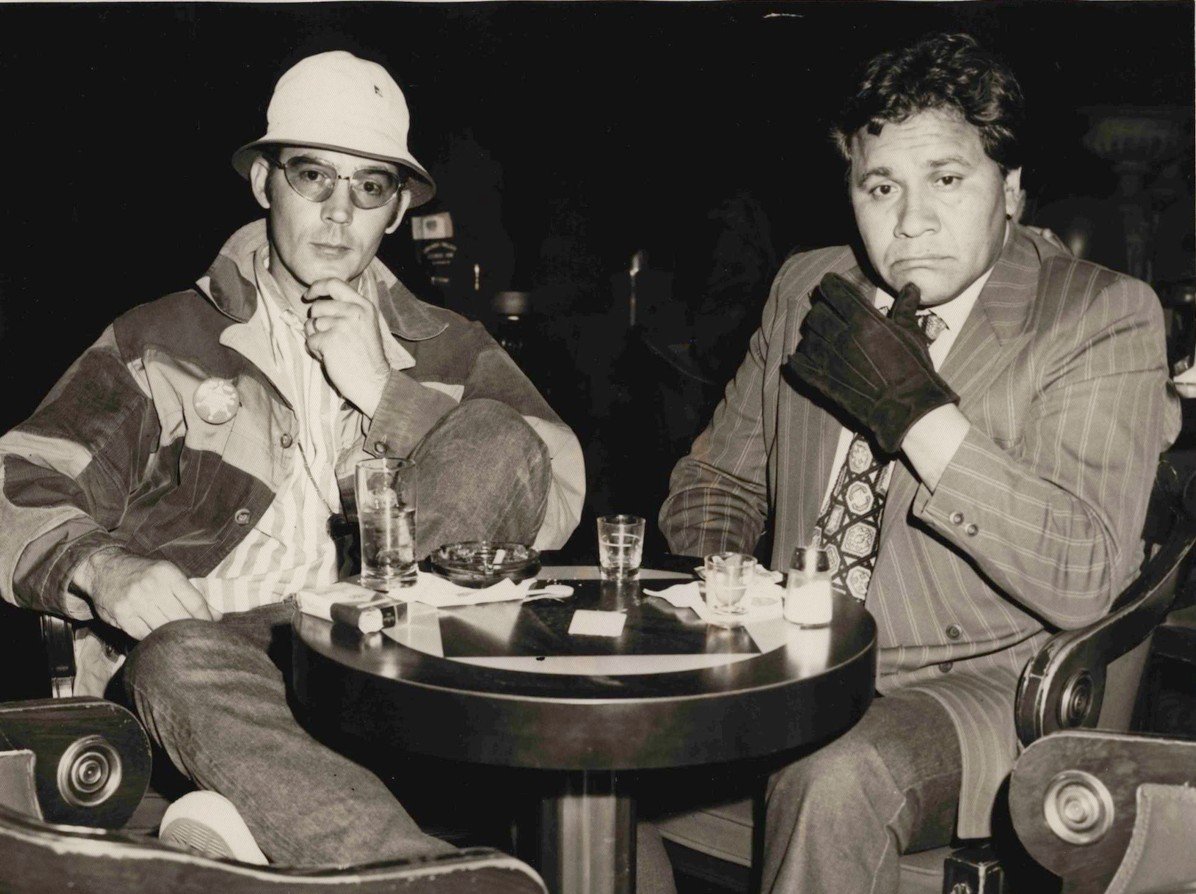

In real life, Thompson was assigned by Rolling Stone magazine to write an exposé on civil rights activist and Los Angeles Times columnist Ruben Salazar, whom LA County Sheriff’s officers “accidentally” shot and killed with a tear gas grenade fired at close range during a Vietnam War protest in 1970. After a week or so of asking tough questions around L.A., Thompson grew scared.

Figuring he might be next, he whisked his main source for the story, attorney Oscar Zeta Acosta, off to Las Vegas to interview him there. Sports Illustrated had hired Thompson to cover the Mint 400, an off-road vehicle race around undeveloped parts of North Las Vegas from March 21-23, 1971.

Sports Illustrated “aggressively rejected” (Thompson’s words) what he submitted as his race coverage. What was supposed to be a 250-word caption instead became a 2,500-word screed on the death of the American dream. So, Thompson instead offered it to Rolling Stone, whose editor, Jann Wenner, scheduled it to run in two parts in future issues.

More than a month later, Thompson and Acosta returned to Las Vegas. They were there to cover the National District Attorneys Association’s Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs for the second half of his Rolling Stone assignment. With only a few minor edits and the addition of the grotesquely hallucinogenic illustrations of Ralph Steadman, the magazine series became the book that would forever entwine Thompson’s name with Las Vegas. He wrote most of it in a hotel room in Arcadia, Calif., while completing Strange Rumblings in Aztlan, his Salazar article for Rolling Stone.

So how much really happened in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream? Based on interviews with witnesses and participants, somewhere around 25%.

The 75% That Didn’t Happen

Let’s start with the legendary contents of Thompson and Acosta’s rental car trunk. In the book, it included “seventy-five pellets of mescaline, five sheets of high-powered blotter acid, a salt shaker half full of cocaine, and a whole galaxy of multi-colored uppers, downers, screamers, laughers, … a pint of raw ether and two dozen amyls,” all gathered during one feverish night in L.A.

This was supposedly the fuel for all the book’s misadventures.

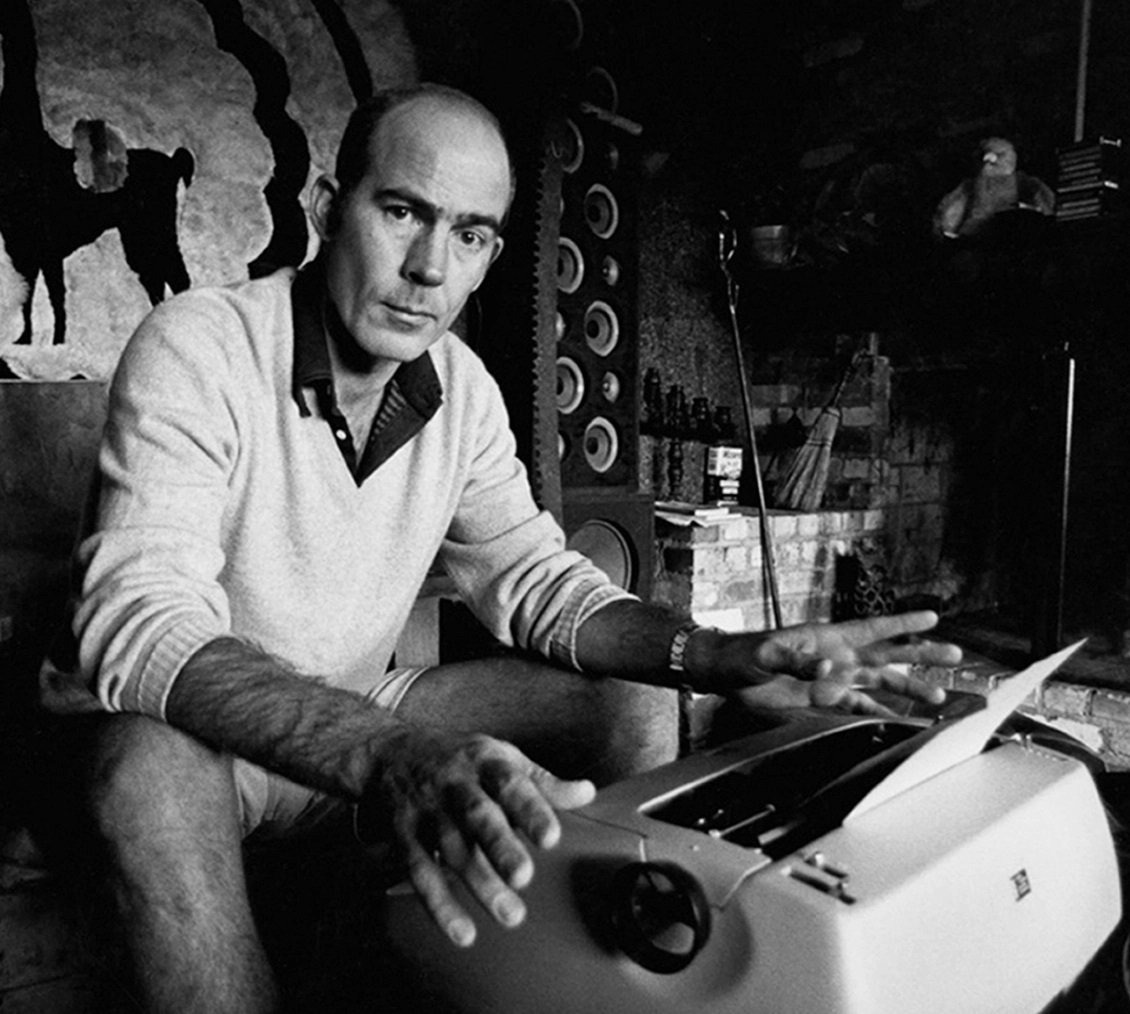

However, in a letter to his Random House editor, published in the 1997 book, Fear and Loathing in America, Thompson admitted there was no actual drug use. The novel “was a very conscious attempt to simulate drug freakout,” he wrote, though he did “at times, bring situations & feelings I remember from other scenes to the reality at hand.” He later wrote to the same editor: ”I have never had much respect or affection for journalism.”

A good chunk of the book’s action took place in Room 1850 of The Mint’s tower (one of 365 rooms that new owner Binion’s Horseshoe permanently closed in 2009). According to Duke’s narration, he and Dr. Gonzo ran up an unpaid room service bill of $29 to $36 an hour for 48 consecutive hours before trashing their room and swiping 600 bars of Neutrogena soap.

“That is something I would have been immediately informed of, but I never heard that,” K.J. Howe, a publicity executive with the Mint at the time, told the Las Vegas Review-Journal in 2010. According to Howe, there was no “Mr. Heem” or any other hotel executive looking for Thompson, Acosta couldn’t have ordered a set of luggage from room service without paying, and no soap was reported stolen.

His concept of what was going on and what was really going on was two different things,” Howe said.

However, Thompson did get the brand of allegedly stolen soap right. (Millionaire real-estate developer Del Webb, who owned the Mint, also sat on the company’s board that made Neutrogena.) Thompson’s eye for detail could imbue an air of believability into the most obvious fantasy.

Another event that never happened is the Debbie Reynolds show at the Desert Inn, at least in the way Thompson reported it. In the book, Duke and Dr. Gonzo witness the opening number (a cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band) before getting bounced for having conned their way in for free.

While Reynolds did play the Desert Inn in March 1971, the singer said she was never informed of any incident resembling this. However, she was sure of one detail that casts suspicion over the entire account: never, she told the R-J, did she perform Sgt. Pepper.

Other embellishments require no witnesses to identify. For instance, the district attorneys’ conference Thompson was assigned to cover by Rolling Stone convened in late April, more than a month after the Mint 400. Yet the book places the events a week apart, joining them through an aborted trip to L.A. punctuated by a traffic stop conducted by a California Highway Patrol officer who supposedly let Thompson go after the author led him on an off-road chase, at 100 mph, with a Budweiser in hand.

“You know,” Thompson quoted the officer, “I get the feeling you could use a nap.”

The 25% That Did Happen

In the 2008 documentary, Gonzo, Thompson and Acosta can actually be heard living out Chapter 9 as they pull into a Boulder City, Nev. taco stand during their second trip to Las Vegas.

“We’re looking for the American dream,” Acosta tells a waitress, “and we were told it was somewhere in this area.”

The waitress turns to the cook, thinking she has just been asked directions to a nightclub.

“Hey Lou,” she says, “you know where the American Dream is?”

That whole chapter is a transcription of that audiotape,” “Gonzo” director Alex Gibney told the R-J in 2010. “So it leads you to believe that some of this stuff is real.”

For the final say, we’ll go to the horse’s mouth. Here’s a blurb from Thompson that was published on the book’s original jacket cover…

“My idea was to buy a fat notebook and record the whole thing, as it happened, then send in the notebook for publication — without editing,” Thompson wrote. “But this is a hard thing to do, and in the end, I found myself imposing an essentially fictional framework on what began as a piece of straight/crazy journalism.”

Look for “Vegas Myths Busted” every Monday on Casino.org. Visit VegasMythsBusted.com to read previously busted Vegas myths. Got a suggestion for a Vegas myth that needs busting? Email corey@casino.org.

Related News Articles

VEGAS MYTHS BUSTED: The Strip is Where Old Music Acts Go to Die

VEGAS MYTHS BUSTED: Videos Never Displayed on the Sphere

Most Popular

FTC: Casino Resort Fees Must Be Included in Upfront Hotel Rates

Genovese Capo Sentenced for Illegal Gambling on Long Island

NBA Referees Expose Sports Betting Abuse Following Steve Kerr Meltdown

UPDATE: Former Resorts World & MGM Grand Prez Loses Gaming License

Most Commented

-

UPDATE: Whiskey Pete’s Casino Near Las Vegas Closes

— December 20, 2024 — 30 Comments -

Caesars Virginia in Danville Now Accepting Hotel Room Reservations

— November 27, 2024 — 9 Comments -

UPDATE: Former Resorts World & MGM Grand Prez Loses Gaming License

— December 19, 2024 — 8 Comments -

FTC: Casino Resort Fees Must Be Included in Upfront Hotel Rates

— December 17, 2024 — 7 Comments

Last Comments ( 2 )

Fact or fiction be damned, it's the funniest depiction of Las Vegas in the 70's ever written. And the description of covering The Mint 400 as similar to viewing an Olympic swim meet in a pool full of talcum powder is Pulitzer-worthy sportswriting.

That's a lot of soap