VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Howard Hughes Bought Silver Slipper Just to Dim its Sign

Posted on: January 3, 2025, 06:55h.

Last updated on: January 1, 2025, 07:28h.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “Vegas Myths Busted” publishes new entries every Monday, with a bonus Flashback Friday edition. Today’s entry in our ongoing series originally ran on May 1, 2023.

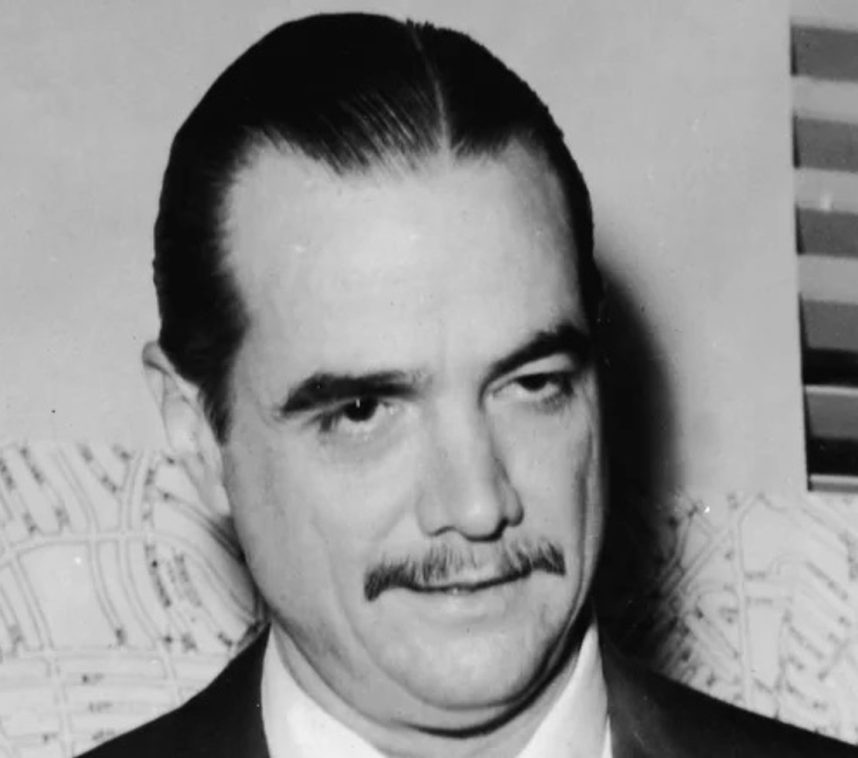

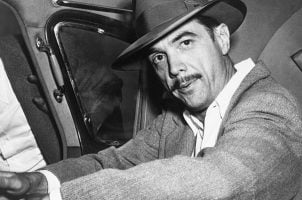

This is already our second Howard Hughes myth, and there are still a bunch left to bust. Supposedly, the world-famous aviator and movie tycoon began his famous buying spree of Las Vegas casino hotels, partially freeing the Strip from the shackles of mafia ownership and paving the way for the age of corporate ownership, all thanks to the giant shoe atop the Silver Slipper.

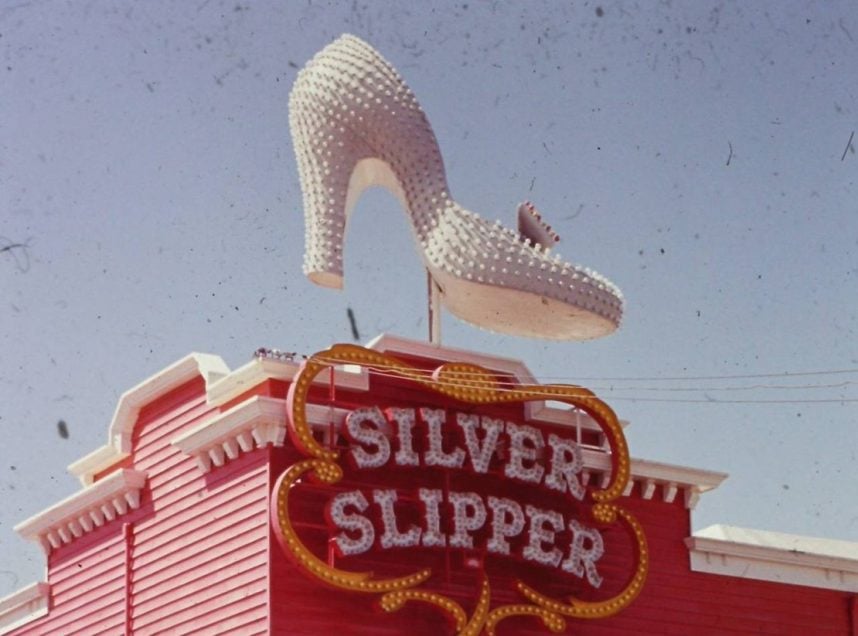

The 12-foot tall, 17-foot wide, rotating high heel was designed by Jack Larsen Sr., a former Disney animator who worked for the YESCO sign company, where he also created the pop-art lamp for Aladdin. Patterned after one of his wife’s pumps, Larsen’s Silver Slipper sign boasted 900 incandescent lightbulbs on the shoe and 80 on the bow. It was installed in late 1954 or early 1955 and was deployed until the resort closed in November 1988.

According to the story, the shoe, located directly across the Strip from the Desert Inn, which Hughes had taken up since arriving in Las Vegas the day before Thanksgiving in 1966, was too bright for Hughes to sleep at night.

The Silver Slipper refused Hughes’ requests to dim the shoe, the story goes, so he bought the casino hotel and dimmed it himself. This gave the eccentric billionaire a taste for acquiring Vegas hotels, and he bought a bunch more.

This myth has appeared in books including “The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of the American Dream” (2022) and “When the Mob Ran Vegas: Stories of Money, Mayhem and Murder” (2005) and in publications as legitimate as the Los Angeles Times.

As is often the case with urban myths, it also comes in other variations. The one featured on the current version of the Silver Slipper’s Wikipedia entry has Hughes believing that the slipper’s toe “could contain a photographer taking pictures of him.” After several attempts at requesting that the slipper be turned off, according to the entry, “Hughes purchased the casino, turned off the lights, and had the rotating system dismantled.”

Both of those stories are complete nonsense — complete nonsense,” Paul Winn, Hughes’ director of corporate records from 1957 through Hughes’ death in 1976, told Casino.org. “I don’t know where they come up with this stuff.”

Of course, as is usual with Hughes, the truth was as strange as the fiction. We’ll get to that later.

Four Main Problems With This Story

According to Winn and all other accounts of Hughes’ time in his Desert Inn penthouse suite, he kept the drapes drawn 24/7.

- No casino sign’s light or photographer’s lens could possibly have penetrated them. Hughes, no doubt deeply in the grips of mental illness by that point, demanded closed curtains (and windows) to protect him from pollution, sunlight, germs, prying eyes, and nuclear fallout from the regular underground explosions at the nearby Nevada Test Site. According to Winn, Hughes tried getting President Lyndon Johnson to stop those tests, but even he wasn’t powerful enough.

- The dates are wrong. Hughes’ buying spree began in March 1967. He didn’t purchase the Silver Slipper until April 30, 1968.

- The Frontier’s sign was bigger and brighter than the Silver Slipper’s, so it would have annoyed Hughes more.

- We know where the myth came from — an erroneous Las Vegas Review-Journal report that was later retracted.

Gossip and Rumors

Well, it was sort of retracted.

On April 21, 1967, R-J gossip columnist Earl Wilson wrote: “Associates say (Hughes) had them request the Silver Slipper to dim its lights. They refused. His emissaries say he has instructed them to negotiate for the purchase of the Slipper so it will no longer interfere with his sleep.”

Almost a full year later, while Hughes’ Silver Slipper purchase was closing, Wilson published what journalists refer to as a “non-correction correction,” in which he discredited his previous false claim without actually admitting that he was its origin. (There was no internet back then to catch him.)

He’s not closing it down, and he’s not turning out the lights,” Wilson wrote of Hughes’ imminent Silver Slipper takeover on April 17, 1968. “They might even burn brighter than ever.”

Wilson’s follow-up proved too veiled a reference for most readers to even connect it to his original report, which is the one they continued to remember.

What Really Happened

The Desert Inn rented its entire top floor and the floor below it to Hughes and his associates for 10 days. Check-out time came and went, and Hughes didn’t budge. DI co-owners Moe Dalitz and Ruby Kolod freaked. They had already promised the suites to high rollers for New Year’s Eve.

Robert Maheu, Hughes’ top aide, had Teamsters Union president Jimmy Hoffa intervene on Hughes’ behalf, but that only bought a couple of more weeks. Maheu then suggested purchasing the DI to his boss as the only solution. And that’s how Hughes’ famous buying spree began.

“Hughes never intended to buy a hotel — he just wanted a place to sleep,” Maheu told PBS in 2005.

As mentioned earlier, the truth is usually as strange as the fiction with Hughes.

On March 27, 1967, Hughes and Dalitz agreed on a price: $13.2 million, far more than the DI was worth. Hughes then purchased the Sands for $14.6 million, the Frontier for $23 million, the El Rancho Vegas for $7.5 million, the Castaways for $3 million, the unfinished Landmark for $17 million, and the Silver Slipper for $5.4 million.

“He bought the Silver slipper because it was available, no other reason,” Winn told Casino.org. “I know. My name was on the gaming license because I was a corporate officer.”

Asked if he knew why the slipper sign eventually stopped rotating, Winn replied: “My guess would be that the rotating mechanism broke, and probably nobody bothered to fix it.”

Recent History

The Silver Slipper was sold in 1988 to hotelier Margaret Elardi for $70 million. She demolished it and turned it into a parking lot for the Frontier, which she also owned. Fortunately, the slipper and its sign were salvaged and retired to YESCO’s boneyard, which later became the Neon Museum’s collection.

Yet another variation on the myth had Hughes ordering concrete poured into the rotation mechanism to jam it. According to the Neon Museum, no concrete was found in the mechanism when they acquired the sign.

In 2009, the museum restored the sign and installed it, along with other vintage Vegas neon signs, in a median along Las Vegas Boulevard North, where it still shines today.

Look for a new “Vegas Myths Busted” every Monday on Casino.org. Visit VegasMythsBusted.com to read previously busted Vegas myths. Got a suggestion for a Vegas myth that needs busting? Email corey@casino.org.

Related News Articles

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Showgirls Still Dance on the Strip

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Actor Lee Marvin Shot Vegas Vic with an Arrow

VEGAS MYTHS BUSTED: Near Myths — Stories So Wild, They Seem Fake But Aren’t

Most Popular

Jackpot News Roundup: Two Major Holiday Wins at California’s Sky River Casino

Oakland A’s Prez Resigns, Raising Questions About Las Vegas Move

MGM Osaka to Begin Construction on Main Resort Structure in April 2025

Most Commented

-

UPDATE: Whiskey Pete’s Casino Near Las Vegas Closes

— December 20, 2024 — 33 Comments -

Zillow: Town Outside Las Vegas Named the Most Popular Retirement City in 2024

— December 26, 2024 — 31 Comments -

Oakland A’s Prez Resigns, Raising Questions About Las Vegas Move

— December 27, 2024 — 9 Comments -

Caesars Virginia in Danville Now Accepting Hotel Room Reservations

— November 27, 2024 — 9 Comments

Last Comments ( 2 )

Sounds like I could relate my father and mother owned a woodcraft shop not far from that sign that that we co-owned with another couple who was stated to be my godparents something happened between the partners and in the middle of settlement agreement we moved to a different state where my father passed away not long after leaving and the settlement was still in the air I was too young to know all the details but I know it was closed down until recently I randomly looked it up and it said it was up and running with my dad's name still titling the company under copyright laws

Great piece on a very weird genius