VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Howard Hughes Left $156M to a Dude Who Once Gave Him a Lift

Posted on: December 13, 2024, 08:04h.

Last updated on: December 13, 2024, 03:30h.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “Vegas Myths Busted” publishes new entries every Monday, with a bonus Flashback Friday edition. Today’s entry in our ongoing series originally ran on Sept. 22, 2022.

When a myth gains pop-cultural legs via a movie, especially a really good one, it can be difficult to dispel. But few serious scholars or former confidants of Howard Hughes believe the story told by Melvin Dummar. He’s the gas station worker who claimed he was left 1/16th of Hughes’ $12 billion fortune simply because he was kind enough to give Hughes the most expensive ride home ever.

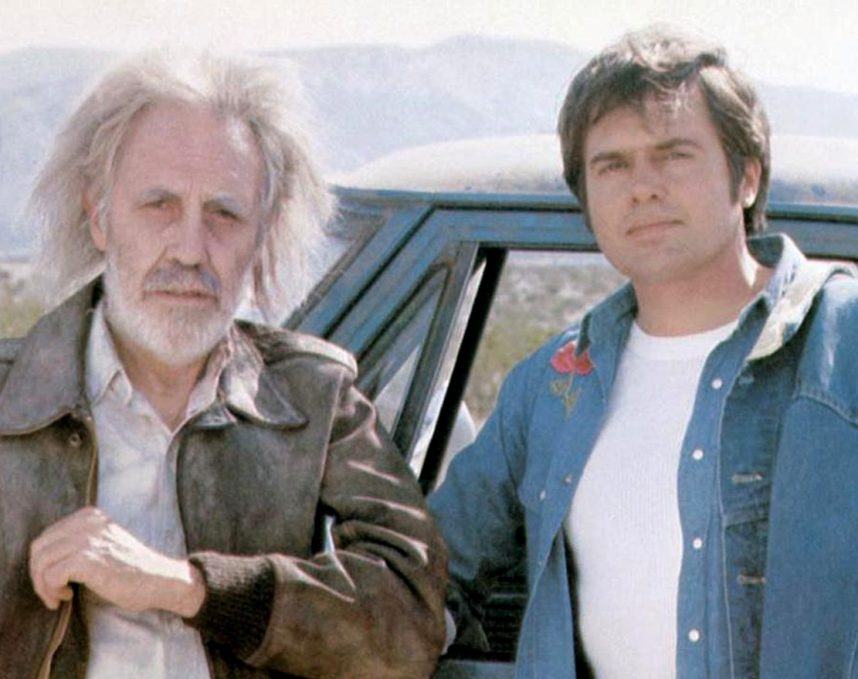

This story was central to the plot of the 1980 Jonathan Demme movie “Melvin and Howard.” Actress Mary Steenburgen won an Oscar for portraying Dummar’s wife. Dummar received $90K for selling the rights to the story, and even landed a bit part in the film playing a bus station reservation agent.

“The problem is that the story is highly improbable — if not impossible,” Geoff Schumacher, author of the 2020 book “Howard Hughes: Power, Paranoia, and Palace Intrigue,” told Casino.org.

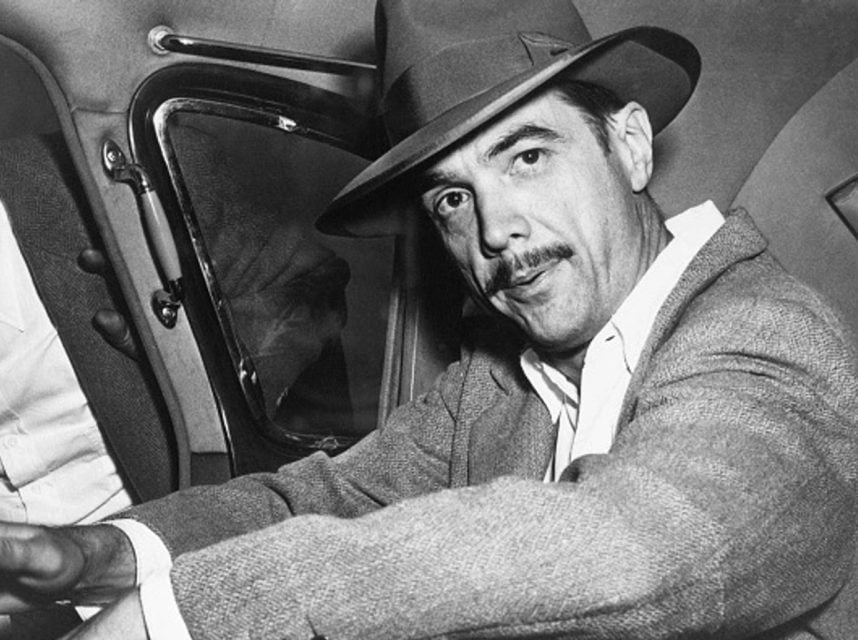

Howard Who?

Howard Robard Hughes Jr. was an American businessman, investor, aviator, film director and philanthropist considered one of the world’s most financially successful and intriguing individuals. He was the Elon Musk of the 1940s. But as the 2004 Martin Scorsese film “The Aviator” suggests, even at the height of his fame and power, he was already very eccentric and dealing with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and chronic pain from multiple plane crashes.

By the time he got to Vegas in 1966, Hughes was a hot mess. For four years, he lived as a recluse in the ninth-floor penthouse of the Desert Inn. He had become addicted to the opioid codeine, which he injected into his arms. And while his obsession with cleanliness caused him to wear tissue boxes on his bare feet to protect them from germs, he rarely bathed or brushed his teeth.

His hair and nails grew long. And, most infamously, he urinated into bottles and kept them around his suite.

Hughes was encouraged to behave however he wished because he owned the hotel. He bought it one night because general manager Moe Dalitz was about to evict him to make room for a New Year’s reservation.

When it comes to Hughes, and the time he spent in Las Vegas, the truth was definitely stranger than fiction.

Myth Understood

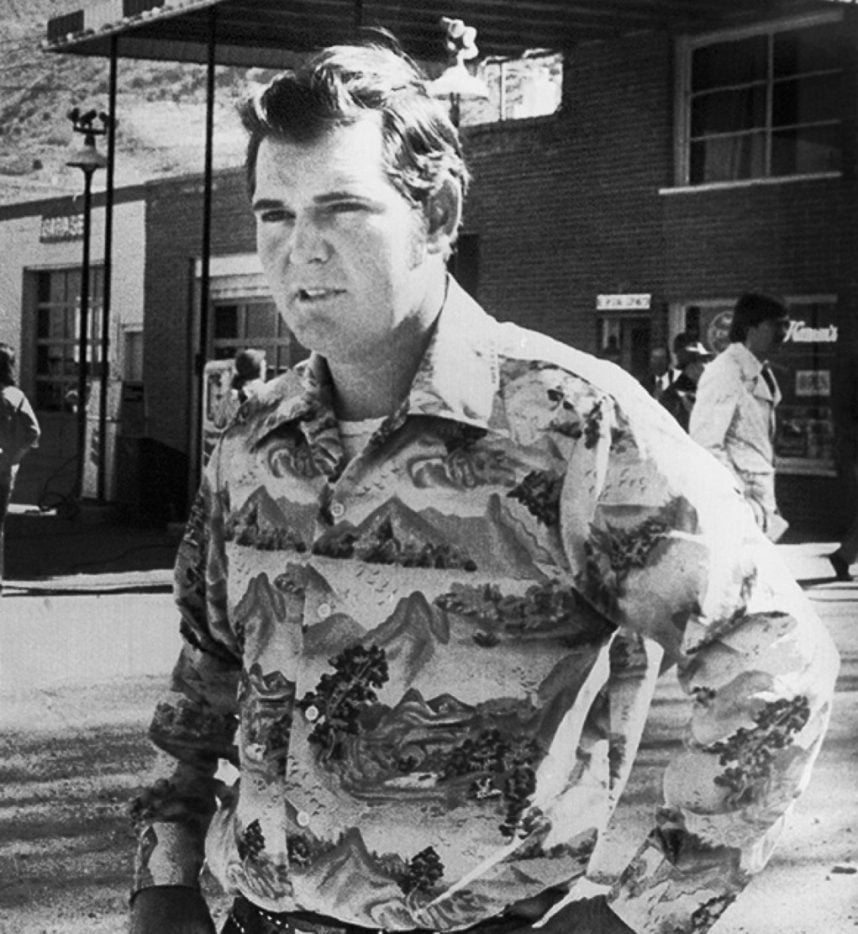

Here’s the story according to Dummar, a native of Gabbs, Nev., who at the time was a 23-year-old magnesium plant worker…

In the winter of 1967, Dummar pulled off US Route 95 for a bathroom break. He had just passed the Cottontail Ranch brothel, about 150 miles north of Las Vegas. When he got back in his car, he spotted a beaten and bruised man on the side of the road. Dummar drove him to Las Vegas and deposited him at the rear entrance to the Sands Hotel, as per his instructions. He also left him with some pocket money. Only in the final minutes of their encounter did the man reveal his identity. Dummar didn’t believe him.

Nine years later, while Dummar worked at a Utah gas station, he claimed, a well-dressed man entered. He left an envelope with Dummar’s name on the counter and exited. After helping a customer, Dummar opened the envelope. It contained a handwritten will signed by Howard Hughes, who had recently died. Dummar was left 1/16 of Hughes’ $12 billion aviation fortune for his long-ago good deed.

The main problem with this story, Schumacher points out, is that Hughes never once left his room at the Desert Inn.“But if he would have wanted to leave, his aides in Las Vegas and in LA would have known about it,” the author and Hughes scholar said. “His every act was carefully recorded each day. Somebody, or more than one person most likely, would have accompanied him wherever he wanted to go. But he didn’t go anywhere, in part because he was quite ill during good chunks of time when he was in Las Vegas.”

By the time Hughes died of kidney failure on an airplane over Texas on April 5, 1976, his 70-year-old body was decrepit. His 6-foot-1 frame weighed 90 lbs. and X-rays revealed five broken-off hypodermic needles in his arms. (To inject codeine, Hughes used glass syringes with metal needles that easily became detached.) Phenacetin, another pain reliever found in his system, may have been the cause of his kidney failure.

The Failure of the Will

Purportedly signed by Hughes on March 19, 1968, the ”Mormon Will,” as it was called because of its discovery in the Salt Lake City headquarters of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, contained many wild discrepancies.

Misspellings abounded, including the name of Hughes’ cousin, William Lummis (spelled “Lommis”). In addition, the will named Noah Dietrich as an executor, someone who left Hughes’ employ on bad terms a decade earlier. And, most preposterously, it referred to Hughes’ famous airplane, the Hughes H-4 Hercules, as the “Spruce Goose.”

It is impossible, no matter what his condition, that Hughes would have described his flying boat as the ‘Spruce Goose,’” Schumacher said. “He hated that nickname, which was given to the giant plane by a reporter. The plane was made of wood, yes, but spruce was not even the type of wood that was used.”

Then there’s the matter of how the will got to where it was found. At first, Dummar claimed to have known nothing about the will. Only after his fingerprint was found on the envelope, he amended his story to include the well-dressed man who entered his gas station. In addition to the will, Dummar claimed the envelope included instructions for him to leave it at Mormon headquarters.

And that’s another oddity. Hughes wasn’t a member of that or any church. He wasn’t a religious person at all, according to Schumacher. Yet, the will also left the Mormon church 1/16th of Hughes’ fortune.

The Mormon Will was ruled a forgery by a Nevada jury in June 1978. In 2006, Dummar filed a second lawsuit in US District Court in Utah against William Lummis, a primary beneficiary of the Hughes estate, whose name was spelled correctly this time. That suit was dismissed seven months later, the judge ruling that the case had been “fully and fairly litigated” in 1978.

Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way

A 2005 book written by retired FBI agent Gary Magnesen claimed to have uncovered new evidence supporting Dummar’s story. According to “The Investigation: A Former FBI Agent Uncovers the Truth Behind Howard Hughes, Melvin Dummar, and the Most Contested Will in American History,” Robert Deiro, Hughes’ personal pilot during that time, confirmed flying Hughes on regular trips to an airstrip behind the Cottontail Ranch. Here, the billionaire would hook up with a prostitute named Sunny, known for having red hair and a diamond embedded in her left incisor.

The reason Dummar found Hughes in the location and the condition he did, Magnesen wrote, is because the brothel had ejected him earlier that evening for being too drunk.

“By all accounts, Gary Magnesen was a first-rate FBI agent,” Schumacher said. “But unfortunately, the conclusions he drew from investigating the Melvin Dummar story are not, in my view, well-supported. The notion that Hughes, with his great fear of germs and reclusive nature, was flying out to a small brothel in the middle of the Nevada desert with a pilot he did not know defies all logic. And the notion that he could do this without anybody in his organization knowing is even more absurd. But hey, people love a good story, so this one has caught the imaginations of a lot of people.”

Dummar died in 2018 in Pahrump, Nev., but not without achieving the immortality he sought, if not the money. No charges were ever filed against him for any crime.

“I met twice with Melvin Dummar, and I liked him,” Schumacher said. “He was a very likable guy, and I think that’s why a lot of people believe his story. People want to believe in an underdog like Dummar, and they have come to expect that powerful people are conspiring against people like him. Sometimes, that is exactly what happens. But not in this case.

“Dummar may have picked up somebody in the Nevada desert and given him a ride to Las Vegas in 1967, but it just wasn’t Howard Hughes.”

Look for “Vegas Myths Busted” every Monday on Casino.org. Click here to read previously busted Vegas myths. Got a suggestion for a Vegas myth that needs busting? Email corey@casino.org.

Related News Articles

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Howard Hughes Bought Silver Slipper Just to Dim its Sign

VEGAS MYTHS BUSTED: Near Myths — Stories So Wild, They Seem Fake But Aren’t

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: Hoover Dam Bodies

VEGAS MYTHS BUSTED: Tony Hsieh Saved Downtown Las Vegas

Most Popular

Genovese Capo Sentenced for Illegal Gambling on Long Island

NBA Referees Expose Sports Betting Abuse Following Steve Kerr Meltdown

UPDATE: Former Resorts World & MGM Grand Prez Loses Gaming License

VEGAS MYTHS RE-BUSTED: The Traveling Welcome to Las Vegas Sign

Most Commented

-

UPDATE: Whiskey Pete’s Casino Near Las Vegas Closes

— December 20, 2024 — 32 Comments -

Caesars Virginia in Danville Now Accepting Hotel Room Reservations

— November 27, 2024 — 9 Comments -

UPDATE: Former Resorts World & MGM Grand Prez Loses Gaming License

— December 19, 2024 — 8 Comments -

NBA Referees Expose Sports Betting Abuse Following Steve Kerr Meltdown

— December 13, 2024 — 7 Comments

Last Comment ( 1 )

It's a great story and movie. Hughes(Jason Robards) sings Melvin's favorite song bye bye black bird. I wish I had given Hughes than .25 lol.