Bill Benter: The World’s Most Successful Gambler Who Used Math To Beat The Bookies

Unlike many other gambling legends Bill Benter does not crave the spotlight.

In fact, he prefers to avoid it all together.

Benter prefers making money over talking about it, and whilst other people gamble for pleasure, to him it’s all about business.

But undoubtedly the most important way he differs from other gamblers is that he will always trust mathematics above his own gut.

That’s because he’s made a career out of using math to swing the odds in his favor.

Originally this took the form of card counting, but Benter was destined for greater things, eventually producing a mathematical algorithm that could accurately and consistently predict the outcome of horse races.

This invention would see him become the richest professional gambler in history.

The mathematical model Benter built not only changed his life forever but also the whole of the gambling industry, popularizing many of the techniques used today including statistical analysis, probability theory, and syndicate betting.

Meaning the man – and the model he built in the 1980s – remain extremely relevant in today’s 21st century.

A Hustler From The Beginning

During his childhood in Pittsburgh, it was clear that Bill Benter had a knack for mathematics.

His love for numbers, problems, and equations soon saw him pursue a degree in physics at Case Western University, one of the top research universities in the United States.

However, during college Benter discovered a much more interesting means of putting his mathematical skills to the test: Card counting.

Like most people in the 1960s and 70s, Benter discovered the ground-breaking gambling method by reading Edward Thorp’s book “Beat the Dealer”.

In 1979, aged 22 and keen to test Thorp’s theory, Benter booked a coach to Las Vegas and began his gambling career.

To fund his early exploits, Benter worked in a 7-Eleven for $3 per hour, staking his wages at the blackjack table whenever he could.

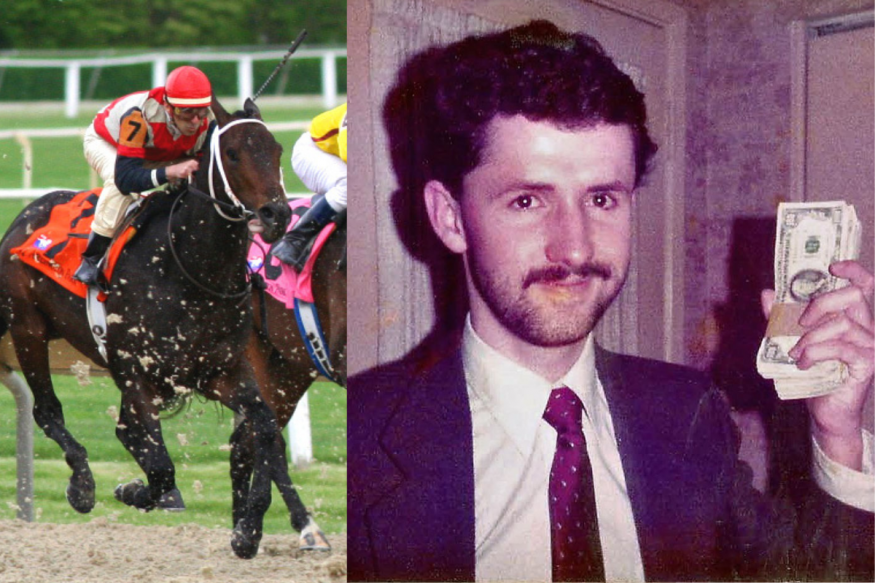

During this time Benter was introduced to Alan Woods (below), an Australian professional gambler who had started his own Las Vegas card counting team.

He soon joined them and earned approximately $80,000 per year.

After a couple of years casinos became wise to the tell-tale signs of card counting and began clamping down on the practice.

Soon, Benter, Woods, and everyone else involved in their team was blacklisted, denying them entry to all casinos in Las Vegas.

Eager to try their skills on a different game, Woods and Benter turned to horse racing.

They agreed to focus on Hong Kong due to the massive popularity of the sport and the huge amounts that were wagered at the twice-weekly races.

This number would reach a staggering $10 billion annually during the 1990s.

Benter’s Betting Model

Before Bill Benter and Alan Woods could begin betting on horse racing, they needed to figure out a means of improving their chances of winning, just as card counting had helped them improve their odds when playing blackjack.

However, the common belief at the time was that horse racing was too unpredictable, with too many uncontrollable variables for a winner to be accurately predicted.

Unperturbed, Benter began researching.

He soon found what he was looking for, an academic paper titled, “Searching for Positive Results at the Track” by Ruth Bolton of Arizona State University.

In this paper Bolton outlines how a horse’s race day performance could be estimated through the examination of several variables. For example, straight line speed, jockey skill, and size.

Benter calculated that by creating a model based on these variables he could determine with greater accuracy the odds of each horse winning.

This meant that he could bet with superior confidence and precision than those who made their choices solely based upon the official odds.

In short, he would have an advantage over all other bettors.

Feeling hopeful, Benter coded his rudimentary system into a few computers and flew to Hong Kong in 1985.

Putting It Into Practice In Hong Kong

The first racing season he and Woods betted on resulted in a total loss of $120,000.

Livid, they soon went their different ways, with Benter spending a couple of years playing blackjack in Atlantic City to raise more money whilst continuing to identify more variables to add to his model.

With each variable identified Benter’s algorithm became slightly more accurate and soon, in September 1988, he felt prepared to try again.

At this point his model factored in about 20 different variables, and it proved to be much more successful than the previous iteration, netting him $600,000 in his first season.

His annual winnings leaped into the millions when Benter began incorporating the Hong Kong Jockey Club’s live betting odds into his system.

The first year he did this, the 1990-91 season, saw him win an impressive $3 million.

As he approached the end of the millennium, Benter’s model examined over 100 variables and had resulted in over $50 million earned throughout the 1997 season alone.

In 2001 Benter’s increasingly accurate model led him to win the Triple Trio, a cumulative bet in which players must accurately predict the first three horses in three different races.

With more than 10 million possible winning combinations, the Triple Trio stood as the ultimate proof that Benter’s model was a sensational success.

His winnings for the Triple Trio alone totaled $16 million, a vast sum of money that he decided to leave unclaimed.

As per the Hong Kong Jockey Club’s ruleset, the winnings were eventually distributed to charities.

With Benter – and Woods, who had his own betting setup built from Benter’s model – winning such vast sums of money, word about their betting systems soon got out.

Many competitors began to set up shop, using a description of Benter’s model, which he published in an academic paper in 1995, to create their own systems.

Competition soon cut into profits and the golden age of mathematical horse race betting was rapidly brought to a close.

When Betting Becomes A Business

Both Bill Benter’s and Alan Woods’s betting schemes were not one-man shows.

Indeed, Benter frequently turned to a whole manner of people, like journalists, analysts, and mathematicians to identify extra variables.

Outside of the model itself, both men hired a team of individuals to place the bets over telephone calls.

When the practice of phoning in bets was banned during the 1997 season, Benter hired a large number of runners to print out betting slips and visit shops all over the city to place his bets manually.

This rudimentary system still resulted in winnings of over $50 million for the year.

However, the business-like nature of the betting schemes led to an investigation by the Hong Kong Inland Revenue Department as any proof that the gambling syndicates acted as businesses would open them up to taxation.

The threat of further investigation – and potentially catastrophic taxes – led Alan Woods to flee Hong Kong and settle in the Philippines.

Although a somewhat legal gray area, the manner of business-like betting popularized by Benter and Woods is now widespread, with perhaps its most famous contemporary example being Zeljko Ranogajec, who incidentally cut his teeth counting cards and betting on horses with both Benter and Woods.

Ranogajec, whose net worth stands above the $400 million mark, indirectly employs approximately 300 people, and bets using a similar mathematical model to Benter on horse racing around the world.

Using Benter’s Model Today

At its peak, Bill Benter’s model factored in over 120 variables per horse and was earning him an estimated $100 million per season.

It is no surprise then that many contemporary gamblers still use Benter’s model – or others inspired by it – today.

In some ways punters looking to improve their odds have an easier time of it than Benter did before the turn of the millennium.

This is largely because statistics are much easier to come by in the digital age.

More data means more variables can be tested, and if proven to predict performance, they can be incorporated into the model.

In order to facilitate this change in betting habits, the Hong Kong Jockey Club, and other entities like it, have begun publishing huge swathes of data to ensure all have equal access to the information.

However, with this analytical approach to betting being widespread, the advantage gained from using a model like Benter’s is limited.

Couple the tons of bettors with rapidly changing betting odds, and you soon find that the earning potential of each win is significantly smaller than it was in Benter’s time.

Many places like the Hong Kong Jockey Club attempt to further level the playing field by notifying punters when large numbers of bets are suddenly put on a horse, thus indicating who syndicates are backing.

This allows the average Joe to mimic the syndicate’s bets, somewhat negating their advantage.

Bill Benter The Philanthropist

Although many people, including Bill Benter himself, estimate his total winnings at the racecourse to total around $1 billion, he is not in fact a billionaire.

And while Benter’s exact net worth isn’t known, he’s widely accepted to be the richest professional gambler on the planet.

As an extremely wealthy man Benter has dedicated himself to helping those less fortunate.

His philanthropy has included donating $1 million to the University of Pittsburgh and $3 million to polio immunization efforts in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and parts of Africa.

He also launched The Benter Foundation in 2007, an organization that has supported a large number of causes focused on improving living standards, boosting the arts, and protecting open spaces in Pittsburgh and across the States.

The foundation has also supported a range of scientific research including the University of Edinburgh’s work on Alzheimer’s disease and The University of Michigan’s research on opioid policy.

Benter also lectures from time-to-time, with topics such as statistics and mathematical probability being taught by him at numerous universities including Harvard, Stanford, and The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Benter lives in his native city of Pittsburgh with his wife Vivian Fung and their son Henry.